Treatment • Dental Crowns

Dental Crowns – Strengthening and Restoring Teeth

Complete guide to crowns: when you need one, when you don't, materials (zirconia, porcelain, metal), costs, safety, and how crowns compare to veneers or implants. Share your x-rays or plan for an independent review tailored to your case.

What is a dental crown?

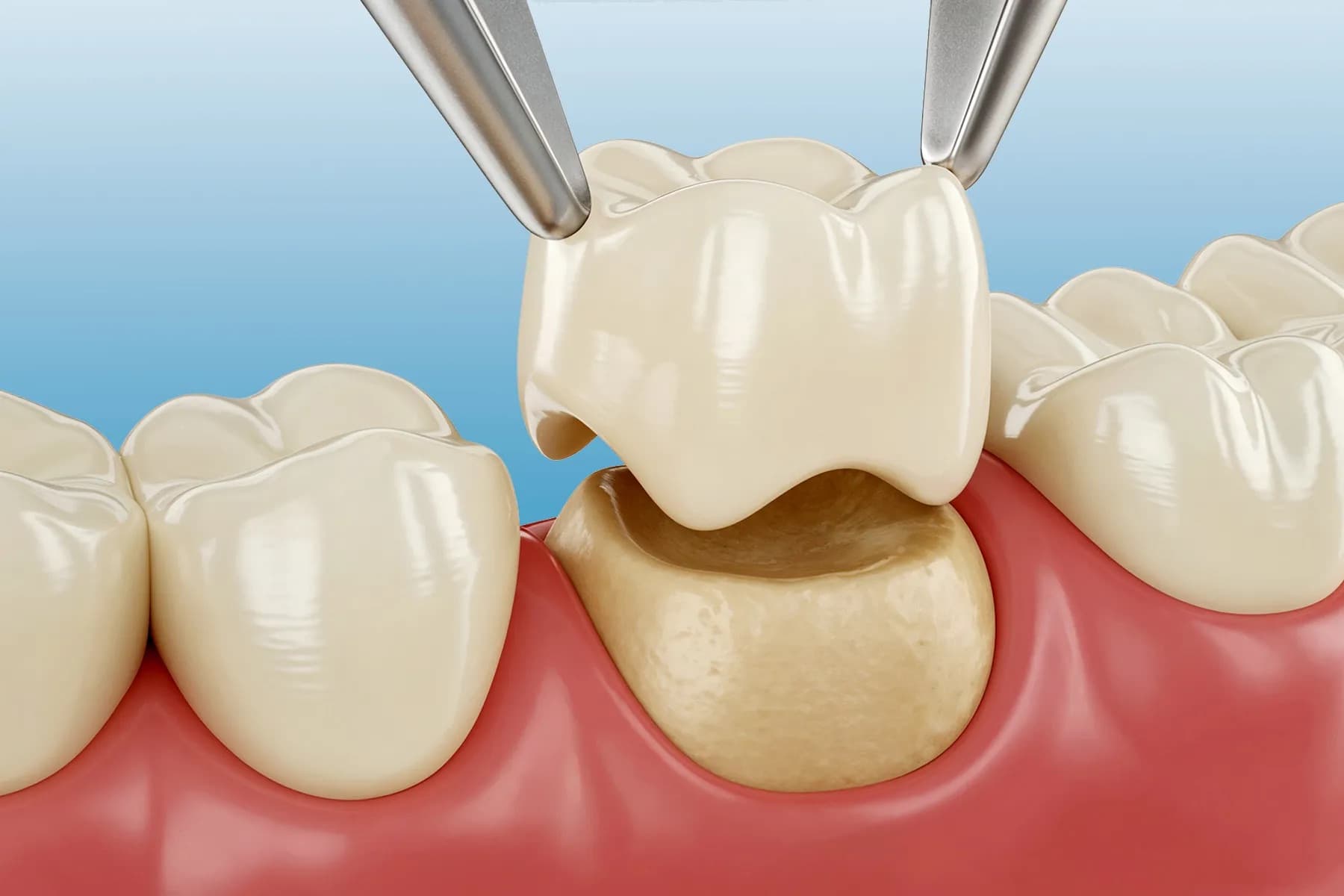

A dental crown is a custom-made cap that covers and protects a damaged or weakened tooth above the gum line. It restores the tooth's shape, strength, and appearance after decay, fracture, or major wear. Crowns can be crafted from porcelain, zirconia, lithium disilicate, metal alloys such as titanium, or layered combinations that balance aesthetics with durability. The crown is bonded or cemented to the prepared tooth, creating a new outer surface that takes the bite forces and seals the underlying tooth structure from further breakdown.

Crowns are different from fillings and veneers. A filling repairs a localized cavity, while a veneer covers only the front surface for cosmetic change. A crown wraps 360 degrees, making it suitable when too much tooth is missing for a filling to stay strong or when a tooth needs protection after root canal therapy. Modern digital design and milling can produce crowns with precise fit and natural translucency, especially with materials like zirconia and lithium disilicate.

Why do you need a dental crown?

You need a crown when a tooth is too compromised to be reliably restored with a filling or bonding alone. Large decay, cracks, or fractures reduce the amount of healthy enamel that can hold a filling. A crown redistributes chewing forces across the whole tooth, lowering the risk of further cracking and sealing the tooth against bacteria. After a root canal, a tooth becomes more brittle, so a crown is often recommended to prevent splitting. Crowns are also used to rebuild teeth with severe erosion, worn biting edges, or large old fillings that are failing.

Cosmetically, crowns can improve the shape and color of teeth with deep intrinsic stains or significant malformation. In implant dentistry, a crown is the visible part attached to the implant abutment. In bridgework, crowns on neighboring teeth support a false tooth between them. The common thread is functional reinforcement: the crown acts like a helmet for the tooth, protecting what remains while restoring a natural look and bite.

How do I know if I need a crown?

Signs you may need a crown include a tooth with a large fracture or a chunk missing, a filling that covers more than half the tooth width, or a tooth that aches when you bite because of underlying cracks. Your dentist may flag teeth with hairline cracks on x-rays or through clinical tests, recommending a crown to prevent a catastrophic split. After a root canal, most back teeth and many heavily restored front teeth benefit from crowns to avoid future fractures.

If you hear that a tooth is “restorable but high risk,” a crown is often the conservative way to save it before it fails. Conversely, if the crack extends below the bone or the tooth has very little healthy structure left, a crown may not be possible, and extraction with an implant or bridge might be safer. A thorough exam with x-rays, crack detection, and bite assessment will clarify whether a crown is the best option or if a simpler filling or onlay would suffice.

When should you not get a dental crown?

Avoid crowning a tooth that lacks a stable foundation. If decay extends below the gum line and there is insufficient healthy tooth above the bone, a crown may not seal well and could fail quickly. Teeth with vertical root fractures, severe mobility from gum disease, or cracks running below the bone are poor candidates; extraction and replacement are usually better. If your bite forces are extreme due to bruxism and you cannot commit to wearing a night guard, even strong crowns can chip or loosen.

Crowns should also be postponed if active gum disease or untreated decay is present elsewhere—stabilizing gum health first improves the long-term outlook. In some cosmetic situations, a minimal onlay or veneer may be preferable to a full crown to preserve more enamel. A careful plan weighs the remaining tooth structure, crack depth, bite, and hygiene habits before committing to full coverage. When the foundations are sound and risks are managed, crowns are predictably successful; when they are not, another approach is safer.

How long does a tooth crown last?

Well-made crowns typically last 10–15 years, and many last longer when the bite is balanced and oral hygiene is good. Modern materials like high-strength zirconia and lithium disilicate resist chipping and fracture better than older porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) designs, but technique matters as much as material. Crowns on back teeth that take heavy chewing forces tend to wear faster than those on front teeth, especially if clenching or grinding is present.

Longevity also depends on how much natural tooth remains, whether a post was used, and how well the margins are sealed. Regular cleanings, flossing around the crown margins, and wearing a night guard if recommended can easily add years to a crown’s life.

How often should crowns get replaced?

There is no fixed schedule. Crowns are replaced when they fail functionally (loosen, fracture, or leak) or cosmetically (visible dark lines, poor shade match, gum recession exposing margins). Many patients keep the same crowns for well over a decade; others need earlier replacement if bite forces are high, hygiene is inconsistent, or the original fit was poor. Routine exams and x-rays let your dentist monitor margins and catch small problems before they require urgent replacement.

How many times can a tooth be crowned?

A tooth can be crowned multiple times as long as there is enough healthy structure to support and seal the new crown. Each replacement removes a small amount of material to create fresh space, so repeated crown cycles gradually thin the tooth. If decay, cracks, or prior reduction leave too little tooth above the gum, a crown may no longer be viable and extraction with an implant or bridge becomes the predictable choice. Preserving enamel and dentin at each stage extends how many times crowning is possible.

How do you know when a crown needs to be replaced?

Warning signs include new sensitivity to biting or temperature, a visible gap at the gum line, recurrent decay on x-ray at the crown margin, or a crown that feels loose or rocks slightly. Chipping of porcelain, especially if it exposes metal underneath, can also justify replacement for strength and appearance. Gum recession that reveals a dark edge or makes the crown look too long is often a cosmetic reason to replace, particularly for front teeth.

If you notice bad taste, trapped food around a crown, or bleeding gums at that site, those can indicate a margin leak or hygiene challenge that needs evaluation. Early intervention—polishing, repairing a small chip, or rebonding a loose crown—can sometimes extend life before full replacement is necessary.

Can a crown be removed and put back on?

Yes, in certain situations a crown can be removed intact and re-cemented. Dentists use crown removal tools or section the cement carefully to preserve the crown when possible, such as during a root canal through the crown or to clean decay at the margin. If the fit remains good and the crown is undamaged, it can often be rebonded. However, crowns may deform or chip during removal, so replacement is common when precise fit cannot be maintained.

Temporary crowns are designed to come off and go back on; definitive crowns are not. If a permanent crown pops off because cement failed but the crown is intact, re-cementation is usually straightforward after cleaning and checking the tooth for decay or fractures.

Do teeth turn black under a crown?

Healthy teeth do not turn black under a well-sealed crown. Darkening can occur if there is recurrent decay under the crown, if the tooth had previous staining from old metal restorations, or if the underlying tooth was dark after a root canal. In porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns, the metal coping can show as a dark line if gums recede, but that is not the tooth turning black. Proper sealing, hygiene, and regular checks help prevent decay-related discoloration beneath crowns.

Will a tooth rot under a crown?

A tooth can develop decay at the crown margins if plaque accumulates and bacteria reach the junction of crown and tooth. The crown itself does not decay, but the natural tooth underneath can if hygiene is poor or the seal fails. Flossing daily around crown margins, using fluoride toothpaste, and attending cleanings are the best prevention. If decay is caught early, it may be possible to repair or replace the crown before the tooth is lost.

Do teeth go bad under crowns?

Teeth under crowns remain alive unless a root canal has been done, so they still need protection. They can develop decay, cracks, or gum problems if oral hygiene or fit is inadequate. Crowns protect by distributing bite forces and sealing the tooth, but they are not immune to failure. Regular checkups allow your dentist to spot changes in the bite, margins, or surrounding gums and address them before the tooth “goes bad.” In stable, well-maintained conditions, crowned teeth can function for many years without issues.

What is the downside of a crown?

The main downside is tooth reduction. To fit a crown, the dentist must remove a layer of enamel all around the tooth, which is irreversible. If reduction is excessive or the remaining tooth is thin, the tooth can become more sensitive or at risk for future root canal treatment. Crowns also introduce a margin where the crown meets natural tooth; if hygiene is poor or the seal is imperfect, decay can start at that junction.

Other downsides include potential bite changes, chipping of ceramic in some materials, and the possibility of needing replacement after years of wear or gum recession. Costs are higher than fillings, and multiple visits are usually required. These risks are why crowns are best reserved for teeth that truly need full coverage.

Are there any downsides to getting a crown?

Yes, beyond tooth reduction and cost, there is a small risk of nerve irritation leading to later root canal treatment, especially on teeth with deep cracks or large decay. If the bite is not balanced, crowns can feel high or cause soreness in the jaw or opposing teeth. Porcelain chipping can occur if you grind or chew hard objects. Finally, crowns require consistent flossing and cleanings; neglect increases the chance of decay around the margins.

Choosing conservative preparation, appropriate material for your bite, and a dentist who takes time to adjust the bite reduces these downsides. Wearing a night guard if you clench further protects the crown and the tooth beneath.

What are the negatives of crowns?

Negatives include irreversible enamel loss, potential sensitivity, higher cost compared with fillings, and the need for future replacement as gums change. Crowns can also complicate flossing if contours are bulky. If margins are placed too deep under the gum, cleaning is harder and gum inflammation may occur. In rare cases, metal allergies can be triggered by certain alloys, though all-ceramic crowns avoid that.

On balance, crowns are highly successful when indicated, but their negatives are real if placed on teeth that could have been managed with a more conservative onlay or filling.

What happens after 10 years of having a crown?

After a decade, many crowns still function well, but natural changes can appear. Gums may recede, exposing crown margins and making a dark line visible on older porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns. Bite forces over time can create micro-cracks or small chips in ceramic. The underlying tooth can slowly darken, altering the shade match. If hygiene has been good and the fit remains tight, the crown can continue to serve; otherwise, polishing, minor repairs, or full replacement may be recommended for function or aesthetics.

What is the most feared dental procedure?

Surveys often cite root canals and extractions as the most feared procedures, largely due to outdated stories rather than current reality. With modern anesthesia and techniques, both are usually comfortable. Crowns are generally well tolerated, but anxiety can arise from the drilling sound or time in the chair. Communicating with your dentist, using noise-cancelling headphones, and taking breaks can make any procedure—including crowns—far less stressful.

How to tell if a dentist is scamming you?

Red flags include pressure to start expensive treatment immediately without clear explanations, refusal to show x-rays or photos, or recommending crowns on many healthy teeth without documented cracks or decay. Vague answers about materials, labs, or warranty are also concerning. A trustworthy dentist will explain options (including no treatment), show you evidence of cracks/decay, discuss pros and cons, and welcome a second opinion.

If you feel rushed, ask for a written plan and take time to compare. Independent reviews of your x-rays and proposed work—like the second opinions we provide—can confirm whether crowns are necessary or if a more conservative approach makes sense.

How much do crowns cost for your tooth?

Crown pricing varies by country, clinic, and material. In North America or Western Europe, a single crown often ranges from USD 900–2,000+ depending on whether it is zirconia, porcelain-fused-to-metal, or lithium disilicate. In Türkiye and similar destinations with lower overhead, high-quality crowns often cost USD 250–700 per tooth. Fees include diagnostics, tooth preparation, temporization, lab fabrication, and fitting. Complex cases—posts, core build-ups, or crown lengthening—add to the total. Always ask what is included so you are comparing like for like.

What is the average cost of putting a crown on a tooth?

“Average” depends on region. A practical midpoint is USD 1,000–1,400 in many large U.S. cities for a single back-tooth crown and USD 300–500 in many reputable Turkish clinics for similar materials. Front teeth sometimes cost slightly more for extra aesthetic layering and shade matching. The lab quality, chair time, and any pre-crown work (core, build-up, gum contouring) influence the final number.

How much is one crown of teeth?

One crown price is set per tooth and scales with material and case complexity. In lower-cost regions, expect a few hundred dollars; in higher-cost regions, expect over a thousand. If multiple crowns are done together, some clinics offer package pricing. Confirm whether the fee covers temporaries, try-ins, shade customization, and follow-up adjustments—omissions here can make a lower sticker price more expensive later.

What is the cheapest way to get crowns?

Lower costs come from choosing regions with lower operating expenses (e.g., Türkiye) and selecting appropriate yet cost-effective materials, such as monolithic zirconia for back teeth. Teaching clinics or public clinics sometimes offer reduced fees in exchange for longer appointments. Beware of ultra-cheap offers that skip temporaries, use low-quality labs, or rush prep time—these can lead to failures and higher long-term costs. Balanced value means verified clinician credentials, reputable labs, and a clear scope of what is included.

What to do if you can't afford a crown?

Discuss interim options with your dentist: a large bonded filling or onlay may stabilize the tooth temporarily, though it may not be as protective. Some clinics offer phased care or financing plans. University dental schools often provide reduced-cost treatment under supervision. Avoid delaying entirely if the tooth is cracked or has deep decay—short-term stabilizing treatment can prevent a fracture that would make the tooth non-restorable. If extraction is unavoidable, plan for a replacement (implant, bridge, or partial denture) when finances allow.

Does insurance cover tooth crowns?

Many dental insurance plans cover crowns partially when they are medically necessary (decay, fracture, post-root canal) but exclude purely cosmetic crowns. Typical reimbursement might be 40–80% of the insurer’s allowed fee, subject to annual maximums that are often low (e.g., USD 1,000–1,500 per year). Pre-authorization can clarify coverage but is not a guarantee of payment. Ask which materials are covered, whether lab fees are included, and what codes the insurer accepts to avoid surprises.

What is cheaper, crowns or implants?

Per tooth, a crown on an existing natural tooth is usually cheaper than replacing a missing tooth with an implant and crown. An implant involves surgery, hardware, healing time, and the final crown—often totaling USD 1,500–4,000+ in high-cost regions. A standalone crown on a natural tooth typically costs less because there is no surgical component. However, if a tooth is non-restorable, a crown is not an option and an implant is the appropriate investment. Comparing prices only makes sense when both treatments are clinically suitable.

In Türkiye, both crowns and implants are more affordable than in many regions, but the ratio remains: saving a solid tooth with a crown costs less than replacing a missing one with an implant. The right choice follows the diagnosis, not just the price tag.

Why do dentists push for crowns?

Crowns are a common recommendation because they are a predictable way to strengthen teeth that are cracked, heavily filled, or brittle after a root canal. A full-coverage crown redistributes bite forces and seals the tooth, lowering the risk of a fracture that could lead to extraction. From a clinical standpoint, a conservative filling on a severely weakened tooth can fail quickly; a crown is considered the safer, longer-lasting option.

That said, not every worn or discolored tooth needs a crown. Minimal onlays, inlays, or bonded restorations can sometimes achieve the goal with less reduction. A thoughtful dentist will explain why full coverage is recommended and what trade-offs exist versus more conservative choices.

Why is my dentist pushing for a crown?

Often it means they see a risk: a large crack line, a filling that spans most of the tooth, a tooth that hurts on biting, or a post–root canal tooth that could split under pressure. They may also be planning ahead if you clench or grind, which increases fracture risk. Ask to see intraoral photos or x-rays showing the crack or decay, and have them explain why a filling or onlay would not be enough in your case.

If the rationale is clear and evidence-based, a crown can be preventive rather than reactive. If the explanation feels vague or rushed, pause and seek a second opinion with your images to verify the need.

Why do dentists insist on crowns?

Dentists may insist when they believe a tooth is at high risk of catastrophic fracture without full coverage, especially after root canal therapy or when only thin tooth walls remain. A fractured cusp that propagates below the bone can render the tooth non-restorable; insisting on a crown is a way to prevent that outcome. There is also a liability aspect: recommending a filling on a structurally weak tooth that later splits could leave both patient and dentist in a worse position.

Insistence should still come with transparency. You should hear why lesser options are insufficient, what material will be used, and how your bite will be adjusted. If those details are absent, request them or seek a second opinion.

Do dentists upsell crowns?

Most dentists recommend crowns for structural reasons, not upselling. However, overtreatment can happen. Warning signs include suggesting crowns on multiple healthy teeth for purely cosmetic reasons without discussing veneers or whitening, refusing to show evidence of cracks or decay, or pressuring you to start immediately. Ethical care involves showing images, outlining alternatives, and respecting your timeline.

Protect yourself by asking: What happens if we try a more conservative restoration first? Can I see the crack or decay on a photo? Which material and lab will you use? Getting an independent second opinion with your x-rays helps confirm whether crowns are truly indicated or if a less invasive option would suffice.

What is the best material for a dental crown?

“Best” depends on tooth location, bite forces, cosmetic goals, and budget. Posterior teeth often benefit from high-strength monolithic zirconia for durability, while highly aesthetic front teeth may look best with layered ceramics like lithium disilicate (e.g., IPS e.max) or layered zirconia. Metal alloys or gold remain extremely durable and kind to opposing teeth but are less aesthetic. The ideal material balances strength with translucency, fits your bite habits, and uses a reputable lab for precise fit.

What is the difference between zirconia and porcelain crowns?

Zirconia is a very strong ceramic that can be used monolithically (one solid piece) or layered with porcelain on top for improved translucency. Traditional porcelain crowns are typically feldspathic porcelain layered over a coping (metal or ceramic) and offer excellent aesthetics but lower fracture toughness than zirconia. Monolithic zirconia prioritizes strength and chip resistance; layered porcelain prioritizes lifelike translucency. Newer translucent zirconias aim to blend both, but porcelain layering can still achieve the most nuanced shading in some cases.

Are zirconia crowns better than porcelain?

Zirconia crowns are generally stronger and more chip-resistant, making them a favorite for back teeth and for patients who clench. Porcelain (feldspathic) crowns can achieve superior translucency and surface texture for front teeth. For many cases, translucent zirconia or lithium disilicate offers a middle ground: high strength with good aesthetics. “Better” depends on whether your priority is durability under load or the most natural light transmission for a visible front tooth.

Are ceramic crowns stronger than porcelain?

Porcelain is a type of ceramic. Strength varies by ceramic formulation. Monolithic zirconia is significantly stronger than conventional feldspathic porcelain and more fracture-resistant than layered porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) in many cases. Lithium disilicate is also stronger than feldspathic porcelain and often used for anterior crowns and some premolars. So, strength is not ceramic versus porcelain, but which ceramic (zirconia, lithium disilicate, feldspathic) and whether it is monolithic or layered.

Are metal crowns better than ceramic?

Metal alloys (including gold) are exceptionally durable, require minimal tooth reduction in some cases, and are gentle on opposing teeth. They rarely chip. However, they are not tooth-colored, so they are usually reserved for back teeth or patients who prioritize longevity over appearance. Ceramic crowns provide a tooth-colored option and can be very strong (zirconia) but may require more thickness for strength. “Better” depends on visibility, bite forces, and aesthetic goals.

Are gold crowns still used?

Yes. High-noble gold alloys are still used, especially for molars in patients who value longevity and minimal wear on opposing teeth. Gold crowns have excellent fit, are very forgiving to the tooth, and rarely fracture. They are less common today due to aesthetics and gold cost, but they remain a top choice for some clinicians in non-visible areas when strength and gentleness to the bite are paramount.

What is the most natural-looking crown material?

Layered ceramics—such as feldspathic porcelain or layered zirconia with porcelain veneering—often deliver the most natural translucency and surface texture for front teeth. Lithium disilicate can also look highly lifelike, especially when carefully shaded and glazed. The skill of the dental lab is critical: even strong materials like translucent zirconia can look natural in expert hands. For back teeth, aesthetics matter less, so monolithic zirconia is usually chosen for strength rather than perfect translucency.

Which crown material lasts the longest?

Gold alloys and high-strength monolithic zirconia have the best track record for longevity and resistance to fracture. Gold has decades of clinical success with minimal wear on opposing teeth. Monolithic zirconia offers similar durability with a tooth-colored appearance, though it can be more abrasive if poorly polished. Longevity also depends on tooth preparation quality, bite adjustment, hygiene, and night guard use for grinders. A well-made crown in either material can last many years when cared for properly.

What are the pros and cons of zirconia crowns?

Pros: very high strength, excellent chip resistance, and minimal risk of fracture even under heavy bite forces or bruxism. Monolithic zirconia can be thinner than some ceramics, meaning less tooth reduction, and newer translucent formulations look more natural than earlier opaque versions. It is also biocompatible and generally kind to gums.

Cons: aesthetic finesse can still be lower than layered porcelain on front teeth, especially in cases needing high translucency. Poorly polished zirconia can wear opposing teeth more than gold or porcelain, so lab finishing and bite adjustment matter. Repairing surface chips is harder than with porcelain, and shade customization can be limited compared with layered ceramics.

Are zirconia crowns stronger than natural teeth?

Yes. Monolithic zirconia is significantly stronger than natural enamel and dentin. It resists fracture under forces that might crack a natural tooth. That strength is helpful for molars and for patients who grind, but it also means careful polishing and bite balancing are needed to avoid excessive wear on opposing teeth. Strength alone does not guarantee success—fit, cementation, and bite alignment remain critical.

Do zirconia crowns crack easily?

No. Monolithic zirconia crowns are among the most fracture-resistant dental ceramics and rarely crack under normal function. Catastrophic fracture is uncommon unless there are underlying design issues—excessive thinning, sharp internal angles, or severe bite imbalance. Layered zirconia (zirconia core with porcelain veneer) can chip in the porcelain layer, but the zirconia core itself remains strong.

Are porcelain crowns good for molars?

Traditional feldspathic porcelain alone is usually too brittle for high-force molars. Porcelain-fused-to-metal or lithium disilicate can be used for some molars if designed thick enough and the bite is well controlled, but many dentists prefer monolithic zirconia for back teeth because of its superior strength and chip resistance. Porcelain excels aesthetically, so it is best reserved for visible areas unless bite forces are low and design is ideal.

Do porcelain crowns stain over time?

High-quality glazed porcelain crowns are highly stain-resistant and do not discolor like natural teeth. Over years, surface glaze can wear slightly, leading to minor roughness that can pick up surface stain, but this is usually managed with professional polishing. Staining at the gum line is more often due to gum recession exposing cement or metal edges, not the porcelain itself. Good hygiene and regular cleanings keep porcelain crowns looking stable long term.

Do porcelain crowns look natural?

Yes—when crafted by a skilled lab and fitted correctly, porcelain crowns (especially feldspathic or layered ceramics) can closely mimic natural enamel translucency, texture, and light reflection. They allow detailed layering and surface characterization that make them ideal for visible front teeth. Natural appearance depends as much on the ceramist’s artistry and shade matching as on the material itself.

Do zirconia crowns look too opaque?

Early-generation zirconia could appear opaque. Newer translucent zirconias look far more natural, but they can still be slightly less translucent than layered porcelain in some cases. For back teeth, the opacity is rarely an issue; for demanding front-tooth aesthetics, layered zirconia or lithium disilicate may offer a more lifelike result. Shade selection, staining, and glazing by a skilled lab can make translucent zirconia look very natural.

Which crown material gives the most realistic appearance?

For the most natural look, layered ceramics (feldspathic porcelain or layered zirconia) and lithium disilicate are top choices, especially for front teeth. They allow nuanced translucency, internal characterization, and surface texture. The lab’s expertise is decisive—an experienced ceramist can make lithium disilicate or layered zirconia appear highly lifelike. Monolithic zirconia can also look good in skilled hands but is generally chosen more for strength than ultimate realism in the smile zone.

Are zirconia crowns more expensive?

Zirconia crowns can be priced slightly higher than some conventional porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns due to material costs, milling technology, and lab processes. However, pricing varies widely by region and clinic. In many practices, zirconia and lithium disilicate are similarly priced, while high-aesthetic layered porcelain cases may cost more because of extra lab time. Always check what is included (temporaries, try-ins, adjustments) to compare value, not just sticker price.

Why are zirconia crowns so expensive?

The cost reflects the zirconia blocks, CAD/CAM milling equipment, sintering ovens, and skilled lab work needed to achieve precise fit and shading. High-strength and translucent zirconias are premium materials. Even so, total price is influenced more by the clinic’s overhead and lab partnership than by raw material cost. In lower-overhead regions like Türkiye, zirconia crowns are often priced much lower than in North America or Western Europe despite using the same materials and technology.

Which crown material is the most affordable?

Porcelain-fused-to-metal and some monolithic zirconia options are often the most affordable tooth-colored crowns. Full-metal crowns (non-precious alloys) can also be economical for back teeth. Gold crowns are usually more expensive due to metal cost. Prices still depend on region and lab quality; choosing a reputable lab and clinician is more important than picking the absolute lowest-cost material, as a poorly made crown can fail and cost more to redo.

Are zirconia crowns safe?

Yes. Zirconia is biocompatible and has been widely used for years in dentistry. It is inert, does not corrode, and has low allergy risk. Proper polishing and bite adjustment are important to minimize wear on opposing teeth, but from a health standpoint zirconia is considered very safe.

Are metal crowns toxic?

Dental alloys used in reputable labs are medical-grade and generally safe. High-noble alloys (including gold) have excellent biocompatibility. Base-metal alloys can cause sensitivities in a small subset of patients, particularly those with nickel allergy, but true toxicity is rare. Using certified labs and specifying nickel-free or noble alloys mitigates concerns. If metal sensitivity is suspected, all-ceramic options like zirconia or lithium disilicate avoid metal entirely.

Can you be allergic to porcelain or metal crowns?

True allergy to dental ceramics (porcelain, zirconia, lithium disilicate) is exceedingly rare. Metal sensitivities are more common, especially to nickel in some base-metal alloys. Symptoms can include gum irritation or lichenoid reactions. Patients with known metal allergies should choose nickel-free alloys or go all-ceramic to minimize risk. Patch testing can be considered in unclear cases.

Which crown material is safest for people with allergies?

All-ceramic options like zirconia or lithium disilicate are safest for patients with metal sensitivities because they contain no metal. If metal is needed (for example, certain frameworks), high-noble, nickel-free alloys are preferred. Always inform your dentist of any known allergies so material selection can avoid potential triggers.